Quick answer: Over-explaining in presentations isn’t thoroughness — it’s a stress response that signals doubt. Executives interpret excessive detail as a lack of confidence in your own recommendation. The fix: audit every slide as either “safety content” (makes you feel prepared) or “decision content” (helps them decide) — then cut ruthlessly. In my experience, most decks are majority safety content that actively undermines your credibility.

Jump to:

A Client Had 65 Slides. I Asked One Question. She Went Quiet for 30 Seconds.

She’d spent three weeks building it. Every slide was polished. Every chart sourced and footnoted. Every possible objection anticipated with backup data.

I asked her: “Which of these slides does the audience need to make a decision — and which exist because they make you feel safe presenting?”

She went quiet. Then: “…most of these are for me, aren’t they?”

Thirty-eight slides were there to manage her anxiety. Not to help the CFO decide. Once she saw it, she couldn’t unsee it — and neither will you.

This is the pattern I’ve watched play out across 24 years in banking boardrooms at JPMorgan Chase, PwC, Royal Bank of Scotland, and Commerzbank. The highest-performing professionals sabotaging their own credibility not by saying the wrong thing, but by saying too much. Over-explaining isn’t a communication problem. It’s a stress response disguised as professionalism.

And the fix isn’t “be more concise.” The fix is understanding why you included each slide in the first place — then having a system to separate what serves you from what serves them.

That system is what I call the Credibility Audit. And once you run it on your own deck, your presentations — and how executives respond to you — will never be the same.

🎯 Stop Over-Explaining. Start Getting Decisions.

The Executive Buy-In Presentation System is a 7-module self-study programme that teaches you how decisions actually get made — and how to structure your presentation so “yes” feels safe. Includes the Credibility Release framework, Decision Definition Canvas, Pressure Response playbook, and AI-assisted workflow. Study at your own pace, with live Q&A calls for support.

Built on 24 years in banking boardrooms. Not theory — pattern recognition from thousands of high-stakes presentations.

Get the Executive Buy-In System → £199

Self-study modules + live Q&A sessions. Join anytime — all released modules available immediately.

First-cohort pricing: £199 is the launch price for this intake only. From next month, pricing moves to £499 (self-study) and £850 (live cohort).

Why Over-Explaining Feels Right But Reads Wrong

Here’s what makes this problem so persistent: the impulse to over-explain comes from a good place. You want to be thorough. You want to show you’ve done the work. You want to anticipate every question so nobody catches you off guard.

These are reasonable instincts. They also signal the opposite of what you intend.

When you present 47 slides of context, methodology, and evidence before reaching your recommendation, the audience isn’t thinking “how thorough.” They’re thinking: “If they need to explain this much, are they sure about it?”

There’s neuroscience behind this. When we’re anxious, we talk more. It’s a measurable stress response — the same mechanism that makes people over-justify when they feel insecure about a decision. Audiences detect this subconsciously. They can’t always name what feels off, but they register it as uncertainty.

The result: you’ve accidentally signalled doubt about the very recommendation you’re trying to get approved.

I watched this happen to a brilliant colleague at Commerzbank. She presented a €50M deal structure for 45 minutes. Flawless analysis. Perfect charts. The Chair’s response: “That was thorough. What did you want us to do?” Her recommendation was on slide 38. By the time she reached it, the room had already decided she wasn’t confident in it.

The seniority paradox makes this worse. Watch any boardroom carefully. The most senior person usually says the least. The CEO speaks last, and briefly. This isn’t laziness — it’s how authority is communicated. But most professionals, as they prepare for senior audiences, add more explanation. They’re signalling junior-ness to the exact people they want to see them as senior.

If your executives keep stopping you mid-presentation, the problem isn’t your content. It’s your ratio of explanation to judgement.

📋 Want the complete Credibility Release framework?

Module 3 of the Executive Buy-In System gives you the full audit tool, Apology Scan reference sheet, and restraint-as-authority techniques.

Get the Executive Buy-In System → £199

Launch pricing — moves to £499/£850 next month.

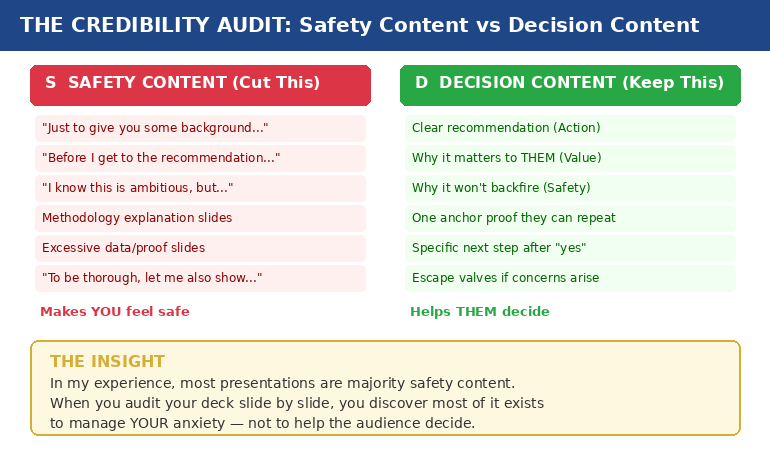

Safety Content vs Decision Content: The Distinction That Changes Everything

Every slide in your presentation falls into one of two categories. Once you learn to see this, you can never unsee it.

Safety content exists to make you feel prepared. It’s the background context, the methodology walkthrough, the 14 case studies, the comprehensive data analysis. It feels essential when you’re building the deck at 11pm. In the room, it signals that you’re not sure what matters.

Decision content exists to help them decide. It’s your clear recommendation, the specific value to them, the reason it won’t backfire, one piece of proof they can repeat to their peers, and a concrete next step.

In my experience, most presentations are majority safety content.

A consultant I worked with showed a client 14 case studies to prove their methodology worked. The client said: “But none of these are in our industry.” One relevant example would have closed the deal. Instead, fourteen irrelevant ones created doubt.

That’s safety content in action. The consultant wasn’t trying to help the client decide. She was trying to protect herself from the question “how do we know this works?” — a question the client never asked.

The three questions every decision-maker silently asks are:

- What happens if I say yes and it goes wrong?

- What happens if I say no and miss out?

- Can I defend this decision to my peers?

Everything that answers those three questions is decision content. Everything else — no matter how impressive — is safety content. And safety content doesn’t just waste time. It actively undermines your credibility by making you look unsure about which information actually matters.

If you’ve ever wondered why your executive presentation structure isn’t landing, start here. The structure probably isn’t wrong. The ratio is.

📊 The Credibility Release Framework: Module 3 of the Buy-In System

Five lessons that transform how you build presentations: why over-explaining destroys credibility (the neuroscience), the Credibility Audit tool for existing decks, the Apology Scan reference sheet, and the “restraint as authority” framework. Plus the Permission to Be Brief audio for cultures that expect “comprehensive” presentations.

Get the Executive Buy-In System → £199

7 modules, 36 lessons, 8 downloadable tools. Designed for busy executives who can’t commit to fixed schedules.

£199 is the first-cohort launch price. From next month: £499 self-study / £850 live cohort.

The Credibility Audit: How to Run It on Your Own Deck

This takes fifteen minutes and will change how you see every presentation you build.

Step 1: Print your deck (or open it in slide sorter view). You need to see every slide at once.

Step 2: Mark each slide with one letter. S for safety content — content that exists because it makes you feel prepared. D for decision content — content that directly helps the audience make their decision.

Be honest. The methodology slide that took you four hours to build? If removing it wouldn’t change whether they say yes or no, it’s an S.

Step 3: Count the ratio. If you’re like most professionals I work with, you’ll find the majority of your slides are S.

Step 4: For every S slide, ask one question: “If the CEO asked me to present this in half the time, would I keep this slide?” If the answer is no, it was never decision content. It was your anxiety asking for an insurance policy.

Step 5: Move the S slides to an appendix. Don’t delete them — that triggers its own anxiety. Put them in backup. If someone asks a question that one of those slides answers, you’ll have it. But you won’t volunteer information that nobody asked for.

A client brought me a 47-slide deck for a steering committee. We reduced it to 12 slides using this exact process. Same information, different structure. The committee approved in 15 minutes — a decision that had been delayed for three months.

The content wasn’t the problem. The ratio was.

🔍 Make this audit repeatable for every presentation.

The Credibility Release Checklist inside the Executive Buy-In System turns this into a systematic, page-by-page diagnostic you can run in minutes.

Get the Executive Buy-In System → £199

Launch pricing — moves to £499/£850 next month.

The Apology Scan: Hidden Phrases That Signal Doubt

Over-explaining isn’t just about slide count. It’s also about language. There are phrases that feel polite and professional but actually function as apologies for your own recommendation.

I call this the Apology Scan. Run through your presenter notes or script and look for these patterns:

“Just to give you some background…” — Translation: I’m not confident you’ll accept my recommendation without extensive justification.

“I know this is ambitious, but…” — Translation: I’m pre-apologising for what I’m about to recommend.

“You might be wondering why…” — Translation: I’m anticipating your objection and defending before you’ve attacked.

“To be thorough, let me also show…” — Translation: I’m padding my case because I’m not sure the core argument is strong enough.

“Before I get to the recommendation…” — Translation: I need you to see how much work I’ve done before you’ll trust my judgement.

Every one of these phrases feels reasonable when you write them. In the room, each one is an unintentional admission of doubt. They tell the audience: “I’m not sure you’ll trust me, so let me earn it first.”

Senior leaders don’t do this. They state what they recommend, why it matters, and what happens next. The absence of hedging is the credibility signal.

I learned this watching a partner at PwC give a 20-minute presentation to a CFO. After five minutes, the CFO interrupted: “I trust you. What do you need?” The partner said: “I need 15 more minutes.” The CFO laughed, approved everything, and left. That partner understood something it took me years to learn: the CFO wasn’t evaluating the content. She was evaluating the confidence.

Why Restraint Communicates Authority (And How to Get There)

Executives judge three things in the first two minutes — before they’ve evaluated a single slide:

- Do you know what you want? (Clear recommendation, not buried on slide 38)

- Do you believe in it? (Restrained delivery, not defensive over-explanation)

- Are you making this easy for me? (Decision-ready structure, not a data tour)

Restraint answers all three. Verbosity answers none.

This doesn’t mean being unprepared. It means being prepared enough to know what to leave out. Cutting content is an act of judgement — and judgement is exactly what executives are evaluating.

The “appendix strategy” solves the cultural challenge. In organisations that expect “comprehensive” presentations, you can be brief in the room while having depth available if asked. Your main deck shows 12 slides of decision content. Your appendix holds 35 slides of safety content. If someone asks “what about the methodology?” — you have it. But you didn’t volunteer it, which signals you know what matters.

This is the difference between a presenter and a decision-maker. Presenters show everything they know. Decision-makers show only what’s needed. Which one do you want to be perceived as?

There’s a reason “great presentation” is the worst feedback you can get. It means they were impressed by your delivery but didn’t feel moved to act. Restraint moves people to act.

How many slides should an executive presentation have?

There’s no magic number. The question is: how many of your slides are “decision content” (helps them decide) versus “safety content” (makes you feel prepared)? A 12-slide deck of pure decision content outperforms a 47-slide deck that’s 70% safety content. Run the Credibility Audit and let the ratio guide you.

How do you present confidently to senior executives?

Confidence in executive presentations is communicated through restraint, not through proving you’ve done the work. Lead with your recommendation, not your research. Cut safety content to an appendix. Remove apology phrases from your script. The absence of hedging is the credibility signal.

Why do executives stop presentations early?

Usually because the recommendation is buried under context. Executives scan for direction in the first 90 seconds. If they find context instead of a clear recommendation, they interrupt — not because they’re impatient, but because they can’t evaluate a proposal they haven’t heard yet.

🏆 The Complete System for Getting Executive Decisions

The Executive Buy-In Presentation System covers everything in this article and far more — from clarifying the decision before you build a single slide, to structuring your message so “yes” feels safe, to handling pressure when executives push back. Seven modules:

- Module 1: Clarify the Decision (eliminate the ambiguity that causes over-explaining)

- Module 2: The Executive Buy-In Structure (Action → Value → Safety → Proof → Next Step)

- Module 3: The Credibility Release (the audit and apology scan from this article)

- Module 4: Reassurance-First Proof (one anchor proof vs ten weak ones)

- Module 5: AI as Execution Engine (90-minute deck creation workflow)

- Module 6: Pressure Response (reframe pushback as risk-testing, not rejection)

- Module 7: Your Personal Executive Playbook (custom rules for your stress patterns)

36 lessons, 8 downloadable tools, live Q&A sessions. Self-study format designed for busy executives.

Get the Executive Buy-In System → £199

Join anytime — all released modules available immediately. Study at your own pace.

⚡ £199 is the first-cohort launch price only. From next month, the self-study programme moves to £499 and the live cohort to £850. This intake locks in the launch rate.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I know if I’m over-explaining versus being appropriately thorough?

Run the Credibility Audit: mark each slide as S (safety — makes you feel prepared) or D (decision — helps them decide). If more than 40% of your slides are S, you’re over-explaining. The acid test: if the CEO asked you to present in half the time, which slides would you cut first? Those were never decision content — they were anxiety management disguised as thoroughness.

What if my organisation expects long, comprehensive presentations?

Use the appendix strategy. Keep your main deck to decision content only (typically 10-15 slides). Move all safety content to an appendix. You’re not being unprepared — you’re being strategic about what you volunteer versus what you hold in reserve. If someone asks a detailed question, you have the slide. But you didn’t dilute your credibility by volunteering information nobody asked for. Over time, your brevity will be noticed — and rewarded.

Doesn’t cutting slides risk looking unprepared or under-researched?

The opposite is true. Knowing what to cut requires more judgement than knowing what to include. Executives recognise this instantly. A 12-slide deck that leads with a clear recommendation signals: “I know exactly what matters.” A 47-slide deck that buries the recommendation on slide 38 signals: “I’m not sure which of this information is important, so I’m showing you all of it.” The first is the presentation of someone ready for the next level. The second is the presentation of someone still proving they belong at this one.

Can the Credibility Audit work for non-slide presentations — like verbal updates or meeting contributions?

Absolutely. The same principle applies to any communication. Before your next verbal update, write down what you plan to say. Mark each point as S (makes you feel covered) or D (helps them decide or act). You’ll likely find you planned to give three minutes of context before reaching the actual point. Cut the context. Lead with the point. Watch how differently the room responds.

📬 The Winning Edge Newsletter

Weekly insights on executive presentations, decision psychology, and high-stakes communication — from 24 years in banking boardrooms. No fluff. No “10 tips” lists. Just the patterns that actually get decisions.

📋 Free: Executive Presentation Checklist

A quick-reference checklist for structuring any executive presentation — including the safety vs decision content check. Download it before your next high-stakes meeting.

Related reading: The Headcount Request That Got Yes When Everyone Said No · Why Your Nervous System Remembers That Awful Presentation From 2019

Your next step: Open your most recent presentation. Mark every slide S or D. Count the ratio. Then move every S slide to an appendix and see what’s left. That’s your real presentation — the one that communicates confidence instead of anxiety. And if you want the complete system for structuring presentations that get decisions instead of “let’s discuss further,” the Executive Buy-In Presentation System gives you the frameworks, tools, and playbooks to make it repeatable. It’s £199 at the current first-cohort launch price (moving to £499/£850 next month).

About the Author

Mary Beth Hazeldine is the Owner & Managing Director of Winning Presentations. With 24 years of corporate banking experience at JPMorgan Chase, PwC, Royal Bank of Scotland, and Commerzbank, she has delivered high-stakes presentations in boardrooms across three continents.

A qualified clinical hypnotherapist and NLP practitioner, Mary Beth combines executive communication expertise with evidence-based techniques for managing presentation anxiety. She has trained senior professionals and executive audiences over many years, and supported high-stakes funding and approval presentations across industries.